Oman is certainly one of my favorite countries on the planet. Never before have I been to place where antiquity and modernity are balanced so perfectly, where the wilderness is so accessible but remains so entirely wild, and where breathtaking vistas are around every corner. I’ll be making a series of post about Oman as there is so much to discover here but to start with I want to focus on a symbol of desert resilience, prosperity and exuberance, The Frankincense Tree.

One of the many things I love about the Arab world is the ever-present scent of bakhoor. As soon as you arrive at the airport, wandering through a souk, exploring a museum, in a taxi, the sweet, smoky fragrance of bakhoor fills the air. It's more than just a pleasant aroma, it's a gesture of hospitality, tradition, and cultural richness that adds a unique layer to every experience.

Of particular interest to me is the plants that provide the source ingredients of the incense and I was happy to discover a wide variety of species and plant parts are used. Woodchips of Agarwood - Aquilaria malaccensis, sawdust of Sandalwood - Santalum album, roots of Valerian - Valeriana officinalis and oils and resins of numerous species. One ingredient, sourced locally, from where I was staying in Salalah, really stood out, Frankincense.

Frankincense

Most people from the West will be familiar with Frankincense from the Nativity, the birth of Christ as documented in the biblical gospel of Matthew. The three wise men (Magi) from the East brought gifts for Jesus, Frankincense , Gold and Myrrh.

Less commonly known is that the wise men are considered to have come from Oman and that the Frankincense quite possibly would have come from the trees that are native to the Dhofar region, specifically Wadi Dawkah, it being the location that has produced the highest quality of Frankincense on the planet for many thousands of years.

What is Frankincense?

Frankincense, also known as olibanum, is an aromatic resin obtained from trees of the genus Boswellia.

There are several species of Boswellia that produce true frankincense, each with its own unique characteristics and aroma. The most common types are follows:

Boswellia sacra: native to Oman, Yemen, and Somalia. It is considered the most prized type of frankincense, with a deep, balsamic aroma and hints of citrus.

Boswellia carteri: native to the Horn of Africa and Nubia. It has a slightly spicy, woody aroma with a hint of lemon.

Boswellia serrata: native to India. It has a lighter, more lemony aroma than other types of frankincense.

Boswellia papyrifera: native to Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Sudan. It has a sweet, balsamic aroma with a hint of mint.

Boswellia frereana: native to the Horn of Africa. It has a light, citrusy aroma with a hint of pepper.

In addition to these five main species, there are several other species of Boswellia that produce frankincense, but they are less common and often of lower quality.

The species we will focus on for the rest of this post is Boswellia sacra, a truly remarkable plant that can live for centuries, some even reaching 1,000 years old in some of the most extreme habitat on the planet.

Boswellia sacra - Frankincense Tree

I first met these glorious plants at The Museum of the Frankincense Land in Salalah, an interesting museum that is within the grounds of the medieval city of Ẓafār. Now a ruin, Ẓafār acted as an important port for frankincense trade and was visited by many renowned travelers, such as Marco Polo, Ibn Battuta and Zheng He.

Following the visit to the The Museum, the next day I set off to Wadi Dawkah, a UNESCO' World Cultural and Natural Heritage site, located 40 km north of Salalah to witness the wild Frankincense Trees - Boswellia sacra that grow there.

A stony, semi-desert valley is a perfect habitat for the frankincense trees that constitute the main vegetation life in the Wadi and spread over an area of 5 km2 from the total 14.5 km2 of the Wadi. A total of 1,257 ancient perennial trees of varying sizes have been recorded in the area.

The plants come from the Burseraceae family and thrive in dry, arid regions with minimal rainfall (less than 250mm annually) . They can tolerate poor, calcareous soils with limited nutrients, grow particularly well on steep slopes and rocky terrain of the Dhofar mountains and have adapted well to temperatures ranging from scorching highs to cool nights.

The root systems are deep tapping into underground water sources inaccessible to other plants and the leathery leaves coated in a wax/powder minimize water loss by reflecting sunlight. The slow growth of the plants also help conserve resources and ensure survival in challenging conditions.

Plant Form

The trees take on variety of form but I presume the standard form would be single stem that branches high with a dense flat crown. The shrub forms are probably the result of pruning in order to make harvesting of the resin easier. We’ll look at how that is carried out later.

Flowering and Pollination

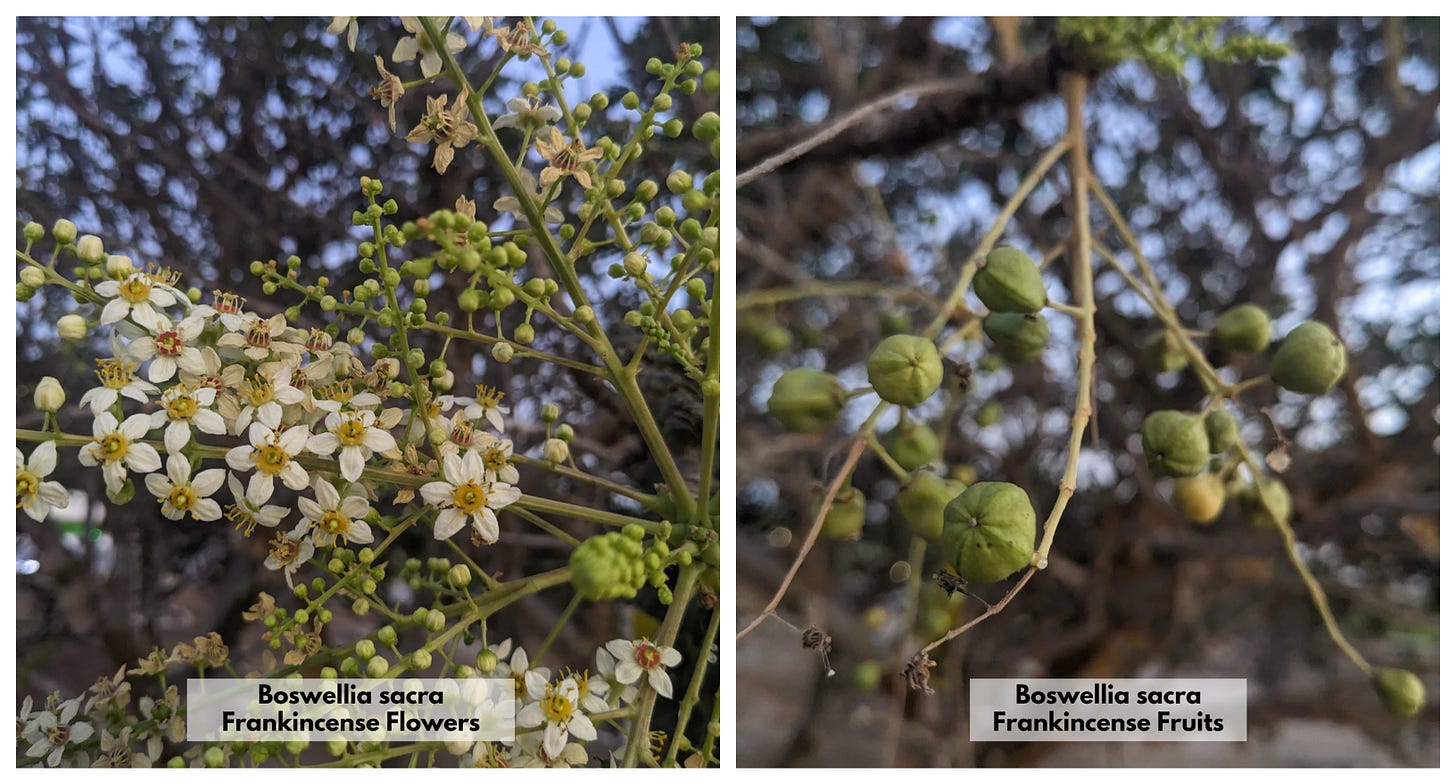

Following the life-giving embrace of the rainy season (The Khareef) that hits the region from June - October the plants embark upon their flowering spectacle. Racemes, adorned with clusters of dainty, creamy-pink flowers, erupt from the tree's branches. The flowering period evidently last as long as February as there were one or two trees with flowers and fruits. The nectary disc with the flower initially awash in a sunny yellow, undergoes a transformation, transitioning to vibrant orange and then a bold red. This orchestrated color change serves as a beacon to potential pollinators, silently communicating the readiness of nectar and pollen.

The plants can self-pollinate but diligent bees and wasps drawn by the chromatic allure and the promise of sweet nectar, flit between blossoms, facilitating cross-pollination that ensures a broader genetic diversity, crucial for the long-term survival and resilience of the population.

Despite successful pollination, germination in these arid conditions remains a formidable hurdle, with only a select few seeds possessing the strength to break through the soil and usher in a new generation.

Regenerative Landscape Design - Online Interactive Course

Want to learn how to design, build and manage regenerative landscapes? Join us on our Regenerative Landscape Design - Online Interactive Course. We look forward to providing you with the confidence, inspiration, and opportunity to design, build and manage regenerative landscapes, gardens, and farms that produce food and other resources for humans while enhancing biodiversity.

You can access the course material at anytime and join the live sessions and interactive forums that run from May - Oct every year. All members of the Bloom Room receive a 500 EUR discount. To take up this offer all you have to do is become an annual subscribers to our Substack and register here with the promo code BLOOM.

I look forward to you joining !

Propagation

The main method used for propagating this fascinating species is via seed and freshness is the key with fresh ripe seeds collected directly from the tree and sown immediately having a much better chance of germinating than older seeds. Even still Boswellia sacra seeds are considered to be difficult to germinate and given the right condition, the germination rate is between 0% to 8%.

The hard seed coat benefits from scarification, such as nicking with a file or soaking in warm water, to improve water uptake and germination and a well-draining, sandy potting mix is ideal. Sowing the seeds shallowly and keeping them moist but not waterlogged is essential. Water deeply but infrequently, letting the soil dry between waterings as overwatering can be detrimental.

Mimicking the tree's natural warm, dry climate with good drainage is crucial as is providing bright, indirect sunlight and avoiding harsh midday sun.

I was surprised to see that seed sown in the ground at the plantation site had put on around 60cm off growth within the first year (unless a local working at the site misunderstood my question or I misunderstood his answer).

Ecology

The shade provided by the trees offer shelter for other plant and animal species. I saw many examples of various other herbs and small shrubs growing under and around the shade of these trees.

During blossoming times The flowers support a diverse insect population of bees, wasps, flies, butterflies, and ants that provide food for the birds and reptiles.

As you walk around what appears as vast areas of empty stony desert the scurrying of a reptile will often break the perfect silence. Fortunately the Carter's rock gecko - Pristurus carteri will often stand perfectly still after the initial flush so you can get a closer look.

For humans Frankincense resin has for millennia been a crucial source of income for local communities and is used in a number of ways.

Frankincense Uses

Incense: Frankincense is a popular incense ingredient, used for religious ceremonies, aromatherapy, and meditation. In Yemen, it is the main Bakhoor choice of the people.

Perfume: Frankincense is incredibly powerful as an ingredient – so it’s only generally used in small doses, except in perfumes designed to conjure up the smell of actual incense. But it also works brilliantly as a fixative so around 13% of all perfumes apparently contain at least a trace of frankincense.

Essential oil: The essential oil of frankincense is obtained by steam distillation of the resin and can be used for a variety of purposes, including aromatherapy, massage, and topical application.

Medicine: Frankincense has been used in traditional medicine for centuries. Some studies suggest that it may have anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and other medicinal properties.

Chewing Gum- Not only is Frankincense the bakhoor of choice for the Yemenis they also chew it as a gum. It has a citrusy taste and strong antiseptic and antibacterial qualities.

The Production of Frankincense from Boswellia sacra in the Dhofar Region of Oman

A frankincense tree enters into the production stage when at the age of eight to ten years, as it becomes stronger and able to withstand the production process. At the beginning of April when the temperature starts getting higher, frankincense producers begin the process by wounding the tree in various positions depending on the size of the tree using a putty knife tool with a wooden handle locally called a “Mangaf” . The first wound is called “Tapping” which is carried out through shaving the external layer of the bark, after which a milky white sap leeches out of the wound.

The producers leave the sap to harden for two to three weeks and then collect it as frankincense. The quality and quantity of this frankincense is not great or commercially viable.

The second wounding process called “Alsa>f1”and starts after two to three weeks from the first wounding. The quality and quantity of this yellowish frankincense is good and has commercial value. It solidifies on the tree or on the ground if the tree is prolific. After that the third wounding starts following the same steps of the second wounding and is called “Alsa>f2”.

The production of frankincense is a process that needs experience and practice because the wrong practice may leave behind an unhealthy tree. The average productivity of a fully grown tree is 10 Kg of frankincense per season. The end of the season is called “Alkashem”.

Interestingly, trees that are far from the area affected by the seasonal rains (The Khareef) provide better quality and quantity. The quality of frankincense is determined by the color and purity; the white bluish frankincense free of impurities is considered the best. The quality decreases when the frankincense becomes reddish or mixed with other impurities

Historically, the value of the product derived from its use in religious, medical and incantation rituals and Oman played the main role in giving the tree its value through the trade of frankincense that expanded as far as the Mediterranean, the regions of the Red Sea, Mesopotamia, India and China.

Frankincense Grades

According to the display in the museum in Salalah, Frankincense can be graded in the following categories

Asha’bi refers to the highest grade of Omani frankincense, specifically from the Boswellia sacra tree. It is known for its exceptional quality, distinct aroma, and higher price point. Asha’bi frankincense typically comes from trees growing wild in the mountains of Dhofar, Oman, and is harvested using traditional methods.

Annajdi is from Najd, a region in central Saudi Arabia. It primarily comes from the Boswellia sacra and Boswellia carterii trees. While not as highly prized as Asha’bi. Annajdi frankincense is still considered high quality and known for its warm, balsamic aroma.

Ashazri can sometimes refer to a grade below Asha’bi but still considered premium quality. Ashazri frankincense usually comes from cultivated Boswellia sacra trees and may have a slightly different aroma profile compared to Asha’bi. and it can also refer to frankincense harvested from Jebel Ashaz a specific mountain range in Dhofar, Oman, known for producing high-quality frankincense.

Al-Hojari can sometimes refer to a grade below Asha’bi but still of good quality but might come from different Boswellia species or cultivated trees and it can also refer to frankincense harvested from Jabal Al-Hojr another mountain range in Dhofar, Oman, also known for its frankincense production.

The natural purpose of the resin is to protect against infection and pests with sticky resin acting as a physical barrier, trapping and hindering insects and other harmful organisms. The resin also serves naturally to defend the plant when branch damage occurs, the resin sealing the wound and preventing water loss and infection. Further more, the aromatic compounds in the resin are thought to attract insects like bees and butterflies, that aid in pollination and seed dispersal of the plants.

Threats and Conservation

Although the resin production process itself is thought to be beneficial for the tree's health, over-tapping practices that prioritize short-term gains over long-term health leave trees vulnerable and ultimately hinder their ability to produce the precious resin. The high demand for the product makes this a serious threat for the wild trees. Habitat loss due to deforestation and land degradation is also shrinking the already limited range of these resilient trees.

The Sultanate of Oman is attempting to set an example of broadscale sustainable harvesting techniques, where tapping methods don't harm the trees, alongside community-led management programs that empower local populations to manage resources wisely. Additionally, the establishment of protected areas for frankincense woods, such as the UNESCO site, is intended to safeguard these precious trees and habitat for generations to come.

Six thousands new trees have been planted in the Wadi and there are plans to plant more in the near future.

That’s all for this posts. I’ll be sharing more about the fascinating plants, incredible ecosystems and highly productive ancient and modern polycultures of Oman in the coming weeks.

Support Our Project

If you appreciate the work we are doing you can show your support in several ways.

Become a member of the Bloom Room. A $70 annual subscription to our Substack provides you with access to live sessions, design tutorials, a members forum and more, see details here.

Make a purchase of plants or seeds from our Nursery or Online Store

Joining us for one of our Practical Courses or Online Courses

Comment, like, and share our content on social media.

Want to learn more about Regenerative Landscape Design? Join The Bloom Room!

The Bloom Room is designed to create a space for more in-depth learning, for sharing projects and ideas, for seeking advice and discovering opportunities.

Ultimately, it aims to build a more intimate, interactive, and actionable relationship between members, a way for the Bloom Room community to support each other’s projects and learning journeys, and to encourage and facilitate the design, build, and management of more regenerative landscapes across our planet.

What you can expect as a member of the Bloom Room

As a member of the Bloom Room you can expect;

Access to an interactive forum where you can ask questions, direct what type of content you would like to see as well as share your own content and projects.

Monthly live session featuring general Q&A and tutorials on design software for creating and presenting polycultures.

Live session every month for members to showcase your projects, plans, designs, and gardens, with guest speakers from the community.

Full Access to all of the content on Substack

A 50% discounts on all of our online courses

Future opportunities to join our Global Regenerative Landscape Design and Consultancy Service, with potential roles for those with the will and skill to join our design team.

An opportunity to take part in the group ownership of a Regenerative Landscape. You will find more details on that here.

Become a paid subscriber to our Substack to join. The annual subscription is currently $70 and the monthly subscription is $7 (monthly subscription excludes discounts for products and services) . You can join here, we look forward to meeting you!

that's super interesting, thanks Paul! I wonder if frankincense essential oil can be added to a spray to deter pests, like neem but nicer smelling...